Our good friend, Ron Moore, Esquire writes us “I actually had a client researching lawyers who looked at the Truth About Forensic Science geek of the week posts and liked my answers. It made a difference in who he decided to hire. Thanks!” So, there is a lot of value in www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week Challenge. Try it out today.

Forensic Science Geek of the Week

Thanks to the combined inspiration of Christine Funk, Esquire and Chuck Ramsay, Esquire, a new twist of this blog is being introduced. A weekly fun forensic science challenge/trivia question. The winner will be affectionately dubbed “www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week.”

Rules:

- The challenge will be posted Sunday morning 12 noon EST.

- Answers to the challenge will be entered by responding to this blog post or thewww.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com FaceBook fan page.

- All comments that are answers to this blog will released after 9pm EST.

- The first complete and correct answer will be awarded the envious title of “www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week”

- “www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week” is entitled a one time post of his/her picture on this blog and the www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com FaceBook fan page. The coveted title will be his/her for that week. Additionally, a winner will be allowed one link to one webpage of his/her choice. Both the picture and the weblink is subject to the approval of Justin J McShane, Esquire and will only be screened for appropriate taste.

- The winner will be announced Sunday night.

- A winner may only repeat two times in a row, then will have to sit out a week to be eligible again. This person, who was the two time in a row winner, may answer the question, but will be disqualified from the honor so as to allow others to participate.

- This is for learning and for fun. EVERYONE IS ENCOURAGED TO TRY TO ANSWER THE WEEKLY QUESTION. So give it a shot.

Here it is:

The www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com “Forensic Science Geek of the Week” challenge question. Remember the first full and complete answer wins the honor and also gets his/her photo displayed, bragging rights for the week and finally website promotion.

OFFICIAL QUESTION:

- Forensic Science Geek of the Week Challenge

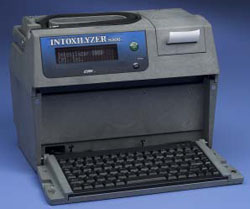

1. What is this called?

2. What technology is it based upon?

3. How does it work?

4. What are it’s limitations?

5. How is it scientifically calibrated?

The Hall of Fame for the www.TheTruthAboutForensicScience.com Forensic Science Geek of the Week:

Week 1: Chuck Ramsay, Esquire

Week 2: Rick McIndoe, PhD

Week 3: Christine Funk, Esquire

Week 4: Stephen Daniels

Week 5: Stephen Daniels

Week 6: Richard Middlebrook, Esquire

Week 7: Christine Funk, Esquire

Week 8: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 9: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 10: Kelly Case, Esquire and Michael Dye, Esquire

Week 11: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 12: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 13: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 14: Josh Lee, Esquire

Week 15: Joshua Dale, Esquire and Steven W. Hernandez, Esquire

Week 16: Christine Funk, Esquire

Week 17: Joshua Dale, Esquire

Week 18: Glen Neeley, Esquire

Week 19: Amanda Bynum, Esquire

Week 20: Josh Lee, Esquire

Week 21: Glen Neeley, Esquire

Week 22: Stephen Daniels

Week 23: Ron Moore, B.S., J.D.

Week 24: Bobby Spinks

Week 25: Jon Woolsey, Esquire

Week 26: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 27: Richard Middlebrook, Esquire

Week 28:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 29: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 30: C. Jeffrey Sifers, Esquire

Week 31: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 32: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 33: Andy Johnston

Week 34: Ralph R. Ristenbatt, III

Week 35: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 36: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 37: Jeffrey Benson

Week 38: Pam King, Esquire

Week 39: Josh Lee, Esquire

Week 40: Robert Lantz, Ph.D.

WEEK 41: UNCLAIMED, IT COULD BE YOU!

Week 42: Steven W. Hernandez, Esquire

Week 43:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 44: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 45: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 46:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 47:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 47:Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 48: Leslie M. Sammis, Esquire

Week 49: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 50: Jeffery Benson

Week 51: Mehul B. Anjaria

Week 52: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 53: Eric Ganci, Esquire

Week 54: Charles Sifers, Esquire and Tim Huey, Esquire

Week 55: Joshua Andor, Esquire

Week 56: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 57: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 58: Eric Ganci, Esquire

Week 59: Ron Moore, Esquire

Week 60: Brian Manchester, Esquire

Week 61: UNCLAIMED IT COULD BE YOU!

Week 62: UNCLAIMED IT COULD BE YOU!

Week 63: Ginger Moss

Rick Holcomb says:

1. The Intoxilyzer 8000

2. Infrared Spectometry

3. Infrared light is shown through the sample chamber. Methyl-group molecules (and perhaps others) block certain frequencies of infrared light. A collector plate is at the other side of the sample chamber. Supposedly, infrared absorption is measured at both 3 and 9 microns. The light that actually made it through the chamber is compared with what was originally shone through. And, through a super-secret source code, algorithms are applied to convert the light measurement to a magic number which is then insisted is the testee’s BrAC.

4. It has a number of limitations including: a) it is non-exclusive (or imprecise) – a number of molecules will block the same frequency of light as does ethyl alcohol (interferents). The result is that alcohol is reported when the machine is actually measuring another chemical, that incidentally are frighteningly common (such as industrial chemicals, camphor, new car smell, and acetaldehyde -which is produced by diabetic’s lungs). b) It is highly susceptible to physiological variations in the test subject. For example, if the subject has GERD, the alcohol in the stomach can get into the mouth, contaminating the sample; hematocrit levels can falsely increase the result because the less liquid there is in the blood, the more concentrated the alcohol will “appear” to the machine; body and breath temperature can falsely elevate the result because of the machine’s misguided reliance on Henry’s Law – and, at least in Hawaii, the calibration-checkers assume that breath temperature is 34 degrees C, despite studies showing that the breath temp., on average, should be expected to rise to 35. Thus, the result is [perhaps] always overstated; c) breathing patterns (which the users cannot and do not attempt to control) can also effect the machine. Hyperventilating v. holding the breath can cause the result to report lower or higher; d) Lack of Sampling controls – the operators of the machine have no knowledge (at least in Hawaii) of the amount of air that is blown into the machine. In fact, as far as I know, Hawaii and all other states, instruct subjects to blow in and keep blowing as hard as they can for as long as they can. As Tom Workman’s studies in Fla and Mass show, the longer you breathe, the higher the result. Thus, instead of measuring 1.1 liters, as the machine supposedly can, the operators are trained to elevate the result (perhaps falsely) – and the other problem is that there can be no comparison because each subject would presumably blow a different volume of breath into the machine. e). The reason that they say they have subjects blow as hard as they can into the machine is because they are interested in “deep lung air.” Why? Ultimately, they believe that Henry’s law applies to the alveoli exchange – so the (incorrect) theory is that the harder you have someone blow, the more likely you will get air directly off the alveoli exchange, and Henry’s Law will apply to reveal how much alcohol is in the blood. The problem is that Henry’s law depends on a constant temperature and pressure, neither of which exists in the human lung, particularly when a person is blowing out as hard as they can. f). Studies show that different partition ratios should be applied to different subjects, yet most states – including Hawaii – have legislated a 1:2100 partition ratio, which results in inflated results (at least in many cases). g) The insides of the bronchial tubes contain moisture droplets, which also contain alcohol. How much alcohol, How many moisture droplets will be introduced into the measured sample, the density of those moisture droplets, etc. are all dependent upon the subject’s own personal physiology – which no man or machine could possibly account for – at least within the confines of a breath test. h). The uncertainty is not reported. Nothing is measured with 100% accuracy or precision. Yet, the probability that the number reported by the machine could actually be the BrAC is not estimated – except in WA and maybe MI. (In Hawaii they don’t even do duplicate testing, which means the result could be a statistical outlier); i) The means by which the machine generated the number is a closely guarded purported trade secret. Where other manufacturers permit defense lawyers to analyze the source code (the software that contains the algorithms and other data that operates the machine – and in this context, very importantly, allows the measurement of the infrared light and the conversion of that measurement to a magic number), analogous to peer-review which is necessary in science, CMI refuses to disclose the code, and literally, even CMI’s customers (the State) only believes the machine works because the guy who sold it to them says so; j) mouth alcohol – alcohol can linger in the mouth for a long period of time. 15 minute and 20 minute observation periods are often inadequate to ensure that all of the alcohol is out of the mouth. The machine has a “slope detector” which is supposed to detect mouth alcohol, but has been demonstrated to operate inconsistently, at best. This is famously shown in various seminars by having the subject eat Wonder Bread and use mouthwash. k) RFI – the machine is susceptible to radio frequency interference – such as using a cell phone. The use of an electronic device could result in an elevated result. Remarkably, CMI advertised the efficiency of the housing of the Intox 5000 as preventing RFI. However, with the 8000, they abandoned that housing in favor of portability. Now, they say that they have magic paint that blocks radio frequencies. Yet the machine remains susceptible to RFI and the error code for RFI does not always appear.

5. This question is a little bit difficult. We must routinely check calibration using a wet bath or dry gas simulator with a known sample. The wet bath simulator is what Hawaii uses. A liquid is heated in the simulator to 34 degrees C, it is agitated, and because of Henry’s Law, the vapor is blown through the 8000 and the results reported. If that is within an “acceptable” margin of error, it is deduced that the machine works “fine.” Your question appears to be what happens when the reading is outside the “acceptable margin of error.” Here, the answer is simple – nothing. What should happen is that the error should be calculated, again, using a known sample. Then, the manufacturer should either adjust the infrared light source (obviously replacing any defective part, whether it be the source, the sample chamber, collector plate, etc.) or, if the error of the machine can be demonstrated as some mathematically comprehensible error (it is off by x% in every test), then I suppose the software (calculations) could be adjusted to give an acceptable result. Obviously, the machine should be tested and it ensured it is reporting acceptable results thereafter.